Before we get into it - yes, I commented on Sunday that this week’s programming would represent a return to normalcy. And, yes, I ended up whiffing entirely yesterday. But you can assuredly look forward to some quality posts for the remainder of the week. Thanks for bearing with me!

DO YOU READ TERMS AND CONDITIONS?

When was the last time you signed a contract? Maybe it was for your lease, which case was probably pretty readable. Maybe it was when you were hired for your current job - there were a few wordy disclaimers, but you still felt like you understood what you were signing. Or maybe it was some kinds of Terms & Conditions, in which case you’re probably part of the ~99% of people who clicked “Agree” without reading the thing.1

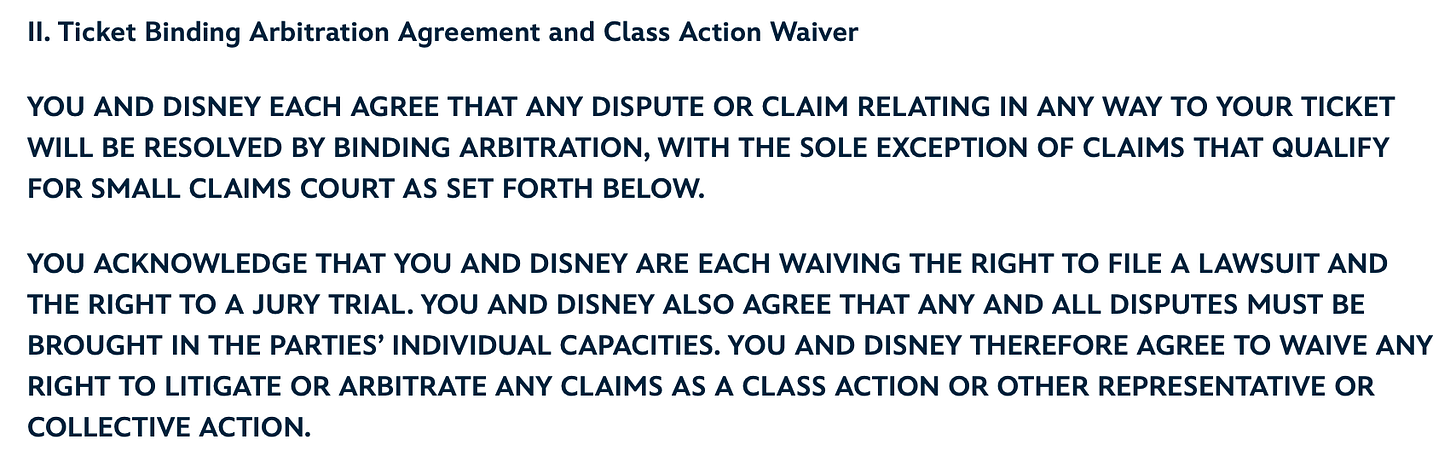

And why should we read those documents? They’re in tiny letters, dozens of pages long, and often filled with seemingly inconsequential stuff like this:

The above was a fun clause that was snuck into Disney+’s Terms and laid dormant until a Long Island doctor died from an allergic reaction at a Disney World restaurant. When her husband attempted to file a wrongful death suit, it turned out that he had (apparently) already waived his right to do so. Fun!

A sillier, but equally illustrative, example would the South Park episode “HumancentiPad”. When Kyle is kidnapped by Apple for human experimentation, it turns out that he only had himself to blame for failing to read the disclosures.

The impenetrability of Terms and Conditions has already been memed to death, but, until recently, I had never stopped to wonder why. Consider that these huge documents have to be written by someone. As strange as it seems, there are entire teams of people - reportedly more than 500 at Apple - who spend their days writing documents that nobody reads.

Back in “AI Ain’t It”, I wrote:

A number of companies are working on AI to write legal documents. Pretty soon, computers will be writing and reading contracts, and there might be some pretty funky things that fly under the radar. Rather than Terminator’s SkyNet initiating a nuclear holocaust, maybe the AI apocalypse will just be the collapse of our legal system.

I would like to walk this back a bit. With apologies to our more legally inclined readership,2 I am starting to think that most legal docs sit and collect dust once they are finalized.

DO LAWYERS LIKE WRITING THIS WAY?

In Even Lawyers Do Not Like Legalese, Martinez, Mollica, and Daniels make a case for the feasibility of simplified documents in our legal system. Now, disregarding the irony of a verbose academic paper criticizing legal documents for being hard to read, they introduce five sensible hypotheses for why “legalese” is so challenging:

Curse of Knowledge - lawyers don’t realize that average Joes can’t understand their writing.

Copy and Paste - legal templates have been reused over time, resulting in traditional language being passed down.

In-Group Signaling - lawyers want other lawyers to think they know what’s up.

It’s Just Business - complexity needs to be maintained so that attorneys can keep charging those phat phees.

Complexity of Information - challenging ideas require challenging language in order to be conveyed properly and precisely.

Note that, although legalese is standard, it is not specifically required by the law.

My favorite experiment from this paper asked participants to rate their own understanding of a legal document, along with what they would expect to be an average layperson’s and an average laywer’s understandings.

The authors focused on how, across the board, the simpler documents were easier to understand. Meanwhile, I found it most interesting that laypeople overrated the ability of lawyers to understand legal docs (in the third bar chart).3 I agree - I would expect the process of interpreting legalese to be easier than “harder than average” after years of practice.

To be clear, the authors of this paper seemed to be nudging the reader in the direction that “simpler docs are better”, which I think is unfair. Consider the “Complexity of Information” hypothesis: if you’re signing Patrick Mahomes to a $500 MM dollar contract, you’re going to want to be specific about any risky activities he is required to avoid, and that is going to require some wordiness. Precision and thoroughness can require long lists.

At the same time, there appears to be some evidence for the “Copy-and-Paste” hypothesis. This paper repeatedly demonstrated attorneys’ preferences for reading simple documents, which leads me to assume that they aren’t exactly chomping at the bit to write the more complicated stuff. Further, papers like Stickiness and Incomplete Contracts speak to the repetitive nature of some agreement types, where contract clauses stay static over time.4

HOW DO YOU EDIT THAT WHICH YOU CAN’T READ?

In broad strokes, the reason for my extended working hours over the past few weeks is that my company has entered crunch time with our legal docs heading for a December deadline. When I say “crunch time”, I mean that we were delivered a 40-page document this past Thursday, and we ended up spending 10 hours redlining5 it so that a response could be sent by Friday.

This was a frustrating experience, as we identified more conceptual errors and definitional/formatting inconsistencies than we would like to see at the 11th hour. The challenges to edits were exacerbated by the use of center-embedded6 and passive sentences7 - some sentences had to be re-read a few times before they made sense.

That’s part of being a customer, though, right? You review the work that you pay for, even if it’s painful, as best as you can. You try to help guide the contractor towards your preferences, so that both sides can come out with a product that they can be proud of.

Our lawyers appear to disagree. Today, we were told:

“Most clients defer to the firm and don’t read through standard documents for issues.”

“A+ funds are happy with the same standard templates that we marked up.”

“Expecting adjustments to improve formatting, reduce redundancy, and address other aesthetic inconsistencies represents a bespoke requirement.”

It seems to me that a standard agreement is mostly pulled from existing templates, where the template is read for relevance but not absolute precision. Extraneous language or redundancy is fine, as long as it doesn’t actually contradict the important parts. Readability is secondary, as long as the attorneys on retainer know what is actually supposed to be happening.

I’m not saying that most legal docs are actually riddled with mistakes. But people are imperfect, even smart lawyers. And I can’t help but wonder whether there are just thousands of documents out there that are plagued with tiny inconsistencies and errors because the legalese is too damn hard to parse.

Don’t worry, I’m also in the 99%.

Looking at you, Lenny and Huan.

I know this one is a bit difficult to read. The bottom wording represents the type of person answering the survey, and the top wording (in this case “Average Lawyer”) represents the type of person being thought about while answering the survey question.

I did not have access to this full article, so I wasn’t able to dig into the data here. We’ll have to trust the authors on this one, but the claim seems reasonable.

In other words, marking up comments and potential corrections.

When a definition is in the middle of the sentence (i.e. In the event that any payment or benefit by the Company (all such payments and benefits, including the payments and benefits under Section 3(a) hereof, being hereinafter referred to as the ‘Total Payments’), would be subject to excise tax, then the cash severance payments shall be reduced).

When the object is used as the subject (i.e. The right to a trial is waived by all parties).

As one of your legally-inclined readers, excellent job!

"maybe it was some kinds of Terms & Conditions" --> fun fact: T&C are called contracts of adhesion, in which one side has all the bargaining power. these are boilerplate and non-negotiable, so there's not much point in reading them anyway; you either take it or leave it.

"most legal docs sit and collect dust once they are finalized" --> yup. until you urgently need to check the contract you signed, only to find out that you have no idea where it is.

"disregarding the irony of a verbose academic paper criticizing legal documents for being hard to read" --> LMAO. some people don't look in the mirror enough.

"challenges to edits were exacerbated by the use of center-embedded and passive sentences" --> for all the preaching from law profs on concision, clarity, and active voice, these weird sentences sure plague legalese.

“'...clients defer to the firm and don’t read through standard documents'” --> wtf? this and the following statements sound like such gaslighting. and i bet the firm was charging exorbitant rates for this "work".